“We looked into the eyes of the beast.”

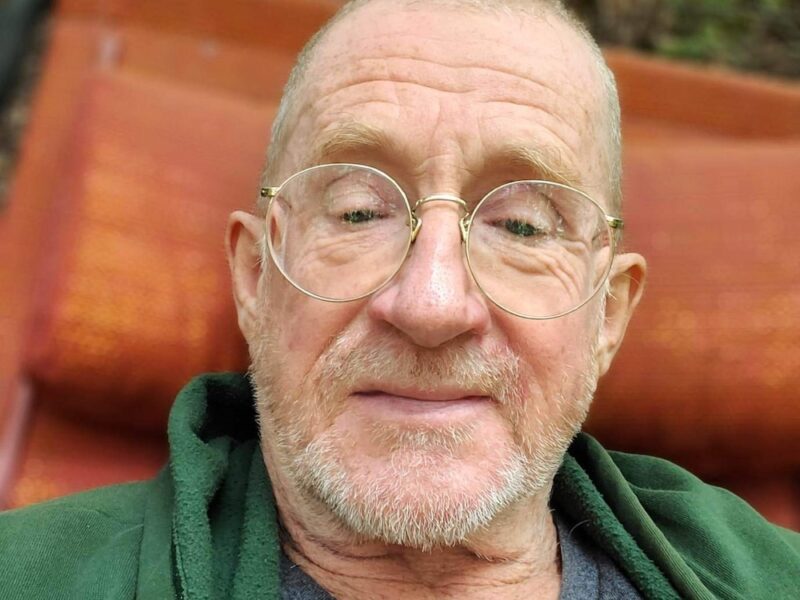

Ken Pite

Ken Pite grew up on a farm by a lake on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. The oldest of six siblings, he has happy memories of going water skiing and building a barn with his family. That affinity for working with his hands stayed with him. In 1996, he saw a newspaper ad for a job as a high school shop teacher in Lytton, BC, in the Interior of the province, about 340 kilometres away from the small city of Duncan where he was living.

He moved to the village to take that job only one week later and kept it until he retired in 2011. To this day, he carries tools with him wherever he goes because he’s “always on the lookout for some little problem to solve.” After retiring, Ken continued to live in what was believed to be the second oldest house in the village, built in the early 1900s. It had a garden and a workshop with a multitude of woodworking and metalworking tools.

Ken made many connections in the Lytton area. He would visit a friend’s fruit stand at the farmers’ market every Friday, which was a “highlight of his week.” He’d meet up with his friend Derek to have long talks about topics like climate change, tell stories, and make each other laugh. Maggie Lord, another longtime friend, lived in the nearby community of Lillooet, BC. Ken taught all of her four children back when they were in high school.

He says Lytton is heavily influenced by Indigenous culture and “full of idiosyncratic individuals.” The people were quite different from each other, but “there was an acceptance that was heartwarming and remarkable.”

His post-retirement life was “quiet.” He drove south to California and Mexico in the winters. He also spent time enjoying his hobbies of yoga, biking, surfing, and gardening. In 2021, Ken’s garden featured 160 garlic plants, raspberry canes, and an apricot tree. However, that summer was so hot and dry that the village was placed on nearly a month-long watering restriction and “the vegetation was simply parched.” Every day from June 27-29 in 2021, Lytton broke Canada’s all-time heat record. It was 49.6℃ on June 29, a record that stands today.

Ken Pite snapped this photo of smoke enveloping Lytton on June 30 and he contemplated whether to return and help others escape. (Ken Pite)

The morning of the fire, June 30, I discovered that my raspberries were dead. The green shoots that would be next year’s fruit-bearing vines had been exposed to so much heat that I could crumble them in my fingers, turn them to powder.

I realized we were living in a powder keg. It was about that point that I said, “Hey, Ken. You’ve often thought about what you would lay aside in the case of an emergency. Today’s the day to do that.” First, I put aside a painting that I valued. Then I got an old briefcase and I put all my backup hard drives into it. Then I got my little travelling file folder that had passports and papers like that. That was by the front door.

The rest of the morning was just reading, browsing online, dealing with feelings of uneasiness and anxiety. I was sitting at my kitchen table and I started on a list of what else I should pack up. It was at that point I smelled smoke. I walked over to my front door and looked across the street, and the bushes were on fire.

One of the realizations I had was, “Ken, there’s nothing you can do about this. This is it. This is going to burn everything.” There was no doubt in my mind whatsoever. I can remember seeing a couple of people looking at the flames with their jaws literally dropped.

A lot of things happened in that split second. One was realizing the fire on the other side of the street wasn’t the problem. The wind was blowing it away from me. The problem was the thick smoke that was travelling down the street in front of me. It was orange, brown and yellow with chunks in it. It was moving 30, 40, 50 miles an hour. The wind gusts were insane.

I started to think of what else I should get but told myself, “Ken, nope, time to go.” I grabbed a handful of clothes that were on a chair on the way out the door and got in my truck. When I drove across the Thompson River and got into the blue sky, everything looked pretty calm and peaceful. I thought, “Maybe I can do something.” So I turned around and I drove back into town. I went to a little deli. The proprietor, Diane Miller, is elderly. I thought she might be there and I could give her a ride. However, the door was locked. I wasn’t thinking all that clearly, in retrospect. If I had, I would have known that the place was closed.

Next door was the assisted living facility. There were a couple of the guys outside on their walkers. I pulled up beside them and talked to the care worker with them who was on her phone. I said, “Time to go.” She said, “I can’t. I’ve got this procedure to follow. I need permission.” I said, “Well, tell whoever you’re talking to that the fire is at the motel,” which was 3 three blocks down the street. The smoke was thick and getting thicker.

I told her I’d stick around and I had plenty of room in my truck and camper for people, and I did. By then, the smoke was so thick that I sat inside my truck because it was nasty stuff. I waited a few minutes and then a bunch of young people showed up, three people in their twenties, thirties. It was very clear to me that they worked there. They were calm and competent and had the situation under control. I realized I was probably just getting in the way, so I got in my truck and drove across the bridge again.

I pulled into a little gas station. While I’m filling up the truck, I’m looking across the river and I’m watching the fire march through the town. It went from one end of the town to the other, a couple of kilometres, in about half an hour. Lots of smoke. Lots of flames that you could see on the outskirts of the fire. By the time I finished fueling up, the flames had already gone halfway through town.

While I was doing that, a young man came up to me, Ahmed, who was the manager of the motel across the street from my little house. Our paths hadn’t really crossed until that afternoon. All he had was a little bag of a few things that he had managed to grab on his way out. He asked me for a ride. I was happy to give it to him. That gave me some purpose.

As I drove out of town, I couldn’t bear to leave. Part of me was going, “You know how this is going to end. The whole thing is burning up. Do you really want to stay here and watch it?” So I turned around and drove up to the lookout. Ahmed was going, “Aren’t we driving the wrong way? Shouldn’t we be driving away from the fire?” I could see a bit, but there was so much smoke. I figured that was not a good place to be. At that point, it was time for Ahmed and I to go north to Lillooet and connect with life.

I headed to Lillooet instinctively. I didn’t really think it out. I’m glad I did. I went to Maggie Lord’s place, a friend of mine. She helped me a lot by just saying, “Yes, Ken, here’s a space you can camp.” I’d open my camper door and it was in a lush green garden. It was a beautiful place to be in many ways. I felt surrounded by compassionate friends, including Maggie’s four children.

A 100 yards away was the evacuation centre. Hundreds of people from Lytton went there. My time that evening was spent looking for familiar faces, a lot of hugging, a lot of sharing stories. There’s a bond there that will never go away. We looked into the eyes of the beast. We all responded in the same way, by fleeing for our lives.

Ken Pite’s home, at top, was one of the oldest in Lytton, with a well-stocked library, elaborate garden and wood and metal working shop where he loved to fix things. Nothing was spared by the wildfire of 2021. (Ken Pite)

Lillooet got smokier and smokier that day. The decision was made to move the evacuees to Merritt. At that point, I decided to go on my own down to Vancouver Island.

I pulled off the side of the road beside a river on my way to Vancouver Island, somewhere around Pemberton. It was beautiful. It was just trees and the river and my truck and camper. The river was loud, so there was the sound of flowing water. There was a little bit of a breeze, so the trees would have been dancing and murmuring. The smells were of pine trees, conifers. There was still a little bit of sun when I first got there. It was very warm, so even when the sun went behind the mountains, it was still quite comfortable. I don’t remember being plagued by mosquitoes.

I sat there that evening and reflected. It was surreal in a sense. I had lost everything that I considered valuable enough to hang onto in seventy years of living. I had a two-thousand-book library. I had tools and hardware that I still used. I had family mementos from my parents, from their parents, photo albums. All of that stuff was simply gone.

I always had this little place that was home, where I would end up going back to. The only thing that was different was that I no longer had that. It was just myself and the truck and the camper. Sitting there by the river, it’s like, “Okay, what has changed? I’m still here, I’m still alive.” I was alive and the sun was shining and the sky was blue and the world was pretty wonderful.

There are points in our lives where, from one moment to the next, things change. I know, when my brother died some years ago, how irrevocable that action was. Things changed, they will never be the same again. So we move on. The choice is always there. There’s a certain element of shock, that grieving of that sense of loss, of that irrevocable change in one’s life.

I would have liked to have had an environment of support people that would have welcomed us back to the site of the fire so we could grieve with our neighbors. In my estimation, what happened immediately post-disaster is that the disaster capitalists moved in: people and corporations that make money off disasters. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that. However, this narrative started to take form that it was too toxic for anybody to go into the village. That narrative took hold and is still enforced today.

We’d be treated like criminals if we’d go in as a group and try to get some closure, try to work through our grief. There was no kindness shown, no compassion shown, no understanding shown. It was cruel and damaged people on top of the loss that we had already experienced. A better balance would have been more concern for the needs of the people involved, the people that lost everything. We should have been the main priority in that situation.

Pite says if Lytton is to avoid another such catastrophe, it must rebuild as ‘a well-watered green oasis in the canyon.’ (Ken Pite)

I think people are holding onto old patterns. Lytton’s burned before and it was always built back the same way. Now the talk is, in order to keep Lytton from burning again, we need to make it out of unburnable materials. Unfortunately, plant life seems to be classified as a burnable material. So a lot of the talk is to limit the green growth rather than encourage it.

From what firefighters tell me, in these situations, buildings burn mostly from the inside out. In my mind, we need to keep the houses cool, and we do that with shade from trees. It’s the direction that nature points us towards, that common sense points us towards. The one way we have to keep Lytton from burning again is by making it a well-watered green oasis in the canyon. We’ve got two big rivers going right by the town. It’s simply an engineering problem to put that water into a reservoir where it can be accessed throughout the town.

We need huge broadleaf deciduous trees that require lots of moisture and that transpire lots of moisture. Trees along the streets and the boulevards so we can go for a walk with a four-legged friend without them burning their feet and without us getting heatstroke, for that matter. Fruit trees in people’s yards so that their houses are shaded.

If we look at the global issue, we’ve got an existential truth right now. Gaia, that thin skin between space and magma, is too hot and is getting hotter, and hotter, faster, and faster. The solution is simple: Garden Gaia into Eden. The only way we have out, in my mind, is to create a green garden planet by encouraging green growth planet wide and through putting that carbon back into the soil, as biochar, where it can be sequestered for hundreds, if not thousands of years. That’s the big lever that we have as a species.

Unfortunately, we have an economic system that one of the big drivers has always been to take what we want from nature with no understanding or regard to the consequences. Our consumer society needs reworking. I’m a woodworker, I love to work with wood. I’ve built houses myself, I’ve built furniture. But forests are carbon sinks. And here we are, in 2022, and maybe we should have a 100-year moratorium on cutting down trees?

I have a lot of despair on a local level because the future that’s been planned for my village is one that’s hot, dry and relatively treeless. Not a place where I particularly want to live. On the global scale, I see us continuing along the same road that we have been on for the last 200 years. How do we restore habitat, restore health? That’s the future industry of the world, I think. The enthusiasm of youth to follow their dreams and not accept no for an answer, that youthful courage that sees a better world and walks towards it—that gives me hope.

This was originally published in The Tyee, on May 15, 2023.

Related Stories

Maggie Lord, Lytton, Canada